As an educator, one of the things that comes up every semester is a student who has "checked out". They stop coming to class and turning in assignments, and you can see their downward trajectory.

What should simply be a small hurdle becomes a 15-foot high tsunami wave for these students. They don't have the psychological resources to go to office hours, work harder, put in the time. So they just let the missed work accumulate until it becomes impossible for them to recover.

When I was an undergraduate I had friends in this place, so it is gut-wrenching to blindly apply a syllabus policy and fail a student in the interest of "fairness". "Fairness" unfortunately means that students on the lower tail of the psychological resource distribution curve get left behind.

What's strange is that this "oh well, tough luck for the student, nothing we can do" sentiment doesn't seem to be quite as prevalent in elementary ed as it is in higher ed. Younger kids having academic trouble have more access to resources to help them - there is a concept of an intervention*. However, for some reason, our society has decided that by the time students are 18 if they struggle in their education it is fully up to them to fix it. Sink or swim.

When faced with a failing student, some people say, "Well, college isn't for everyone", or, worse, "Computer Science isn't for everyone". I disagree. I think everyone is able to do both -- it's just that some people are dealt better hands than others, and our system currently favors those with pocket aces.

_______

(*) In well-resourced and caring schools, that is.

Sunday, November 16, 2014

Sunday, September 7, 2014

Teaching is like children

A new course is like a new baby. You have to feed it, bathe it, calm it, put it to bed, keep it appropriately entertained and distracted. You worry about it a lot, especially when it gets sick, to the point of complete distraction from everything else in your life (your job, showering, etc).

The second time you teach a class, it is like having a toddler. It is slightly more capable, but you need to worry about it choking on errant objects, not looking both ways before crossing the street, and ensuring fried potatoes are not the only vegetable it eats.

The third time you teach a class, it is like having a kindergardener. You worry about it occasionally, like when fights or cdiff break out at school, but overall you are considerably more relaxed.

It is around year three or four that you start to get a little heartsad. You miss the excitement you felt when you found That Perfect Example, or The Hilarious Video, or even that time you discovered those amazing lecture notes from the University of Alburquerque on set theory with the two pigs. The course materials don't need you as much as they used to.

So you putter around, tweaking things here and there, while idly toying with the idea that next semester, by golly, you're going to prep a new class. Just as nature makes parents forget the trauma of pregnancy and the agony of not sleeping for 2-3 years, academia, too makes us forget the birth of a course.

The second time you teach a class, it is like having a toddler. It is slightly more capable, but you need to worry about it choking on errant objects, not looking both ways before crossing the street, and ensuring fried potatoes are not the only vegetable it eats.

The third time you teach a class, it is like having a kindergardener. You worry about it occasionally, like when fights or cdiff break out at school, but overall you are considerably more relaxed.

It is around year three or four that you start to get a little heartsad. You miss the excitement you felt when you found That Perfect Example, or The Hilarious Video, or even that time you discovered those amazing lecture notes from the University of Alburquerque on set theory with the two pigs. The course materials don't need you as much as they used to.

So you putter around, tweaking things here and there, while idly toying with the idea that next semester, by golly, you're going to prep a new class. Just as nature makes parents forget the trauma of pregnancy and the agony of not sleeping for 2-3 years, academia, too makes us forget the birth of a course.

Friday, June 27, 2014

Fight for your right (to publish?)

When you get a rejection, do you call the editor / program officer / etc. and "give them the business"?

I am curious. I never heard of doing this until a natural scientist friend told me this was common practice in her field for journals. ("That's what the boys do," she whispered conspiratorially).

Having been raised to be quiet and well-behaved (*ahem*), when I receive a rejection I usually take it to mean I need to buckle down and write a better paper / proposal. I assumed that was what everyone did. But apparently some people make phone calls.

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Programming Sucks, Implementing Unicorns, and Other Professional Insights

This article by Peter Welch, "Programming Sucks", is probably the best description of our profession I have ever read. Those of you who are computer scientists will read it and say, YES, EXACTLY; those of you who are not computer scientists but think we are mystical beasts from mordor will realize we are not actually mystical beasts. (Though may indeed come from mordor).

Peter's article is so good, I am loathe to quote the clever, funny bits because they're so much better in context; but I have to at least post some some teasers:

Peter's article is so good, I am loathe to quote the clever, funny bits because they're so much better in context; but I have to at least post some some teasers:

Not a single living person knows how everything in your five-year-old MacBook actually works. Why do we tell you to turn it off and on again? Because we don't have the slightest clue what's wrong with it, and it's really easy to induce coma in computers and have their built-in team of automatic doctors try to figure it out for us. The only reason coders' computers work better than non-coders' computers is coders know computers are schizophrenic little children with auto-immune diseases and we don't beat them when they're bad.

...

Most people don't even know what sysadmins do, but trust me, if they all took a lunch break at the same time they wouldn't make it to the deli before you ran out of bullets protecting your canned goods from roving bands of mutants.

Enjoy!

Sunday, April 13, 2014

Google only acquired male parts of startup company; and more #siliconvalleyfail

Article in New York Magazine about a startup company with four men and one woman ("Amy") acquired by Google. Google elected to only hire the four people with their male bits flipped.

The four men werecode monkeys engineers, and Amy was a UX and product designer, and co-founder who contributed tons of ideas. Apparently Google gave massive signing bonuses and salaries to the men, but did not hire her or compensate her during the company acquisition.

Put yourself in this position for just a second. You helped found a company, you contributed major ideas, you got it to the point where Google decides it's worth slurping up. But then:

The four men were

Put yourself in this position for just a second. You helped found a company, you contributed major ideas, you got it to the point where Google decides it's worth slurping up. But then:

Do you have any clue what that feels like? It's horrible. It's people saying: "I don't respect you because of how you were born."

It's impossible to imagine this rejection if you are a majority member. Well, I can tell you - it hurts. A lot. Probably one of the hardest pains out there.

The worst part about me reading this article is that this week alone I heard stories about TWO amazing, brilliant, talented, superstar women completely leave their rockstar jobs to adopt non-rockstar occupations.

Why did these brilliant, talented, incredible women leave their rockstar occupations? Because they couldn't handle the sexism any more. They had no fight left in them.

What can you do? Well, sponsor the heck out of / promote the professional women you know.

1) Talk about women to others: "Jane Smith is doing AMAZING work related to yours, you should check out her papers."

2) Invite women: "Let's invite Jane Smith as a keynote speaker, her research rocks" "Let's ask Jane Smith to lead this project, I think she'd do a fantastic job."

3) Suggest women when you're poaching people: "Let's see if we could recruit Jane Smith to our department."

and, if you're a journalist:

4) Interview women. Some publications do well at this, some are still in the stone ages. There are women scientists out there, and they have opinions and interesting things to say too!

And, if you're google, don't be evil. (Write that one down!).

Labels:

#nogirlsallowed,

#siliconvalleyfail,

sexism

Tuesday, March 25, 2014

Eight little words inculcate imposter syndrome

The great Maria Klawe, ACM Fellow, AAAS Fellow, president of Harvey Mudd, wrote a surprisingly humbling and honest article in Slate on imposter syndrome.

In some ways, this type of article is good for young women in the field, because they figure if superstars like her can feel it, they can feel it too. i.e., "It's normal to feel this way."

Except, it's not normal to feel this way.

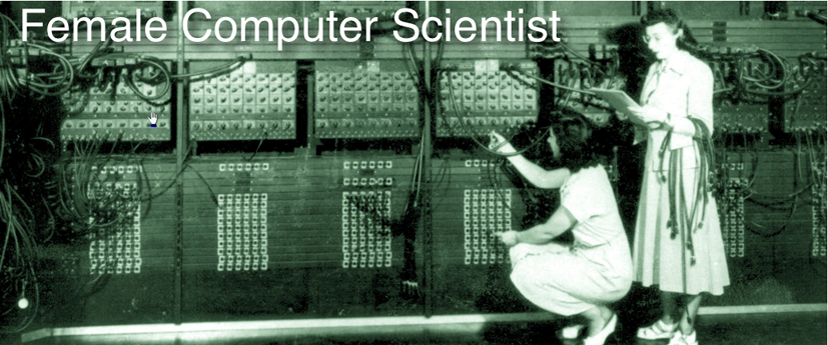

The reason we feel like we don't belong / aren't good enough, is because we've been encultured to believe this since Day 1. The message from the media is passive pink, and rarely are young women cast in roles of lead scientist in film and television. The whiz computer genius in a show usually looks like this:

"That doesn't look like me. Also, he seems really unhappy. I don't belong in computer science."

Readers protest, "But it's just TV! It doesn't matter!"

But it does. This is how kids choose careers. As much as we'd like to think that our annual science outreach visit to our children's classrooms hugely influences students' future career learnings, we're talking marbles vs. Large Hadron Collider. Hollywood is it.

So for the lucky few who manage to beat the cultural odds and enter our field anyway, they have one more major hurdle.

It's not the intellectual requirements of the job.

It's not work-life balance.

And it's certainly not babies!

Nope. It is eight little words that skewer you with a knife. Eight little words that knock you down in one fell swoop.

Eight little words that men never hear.

"You only got here because you're a woman".

Have you ever said this to someone? Have you ever thought this and not said it?

This is an awful, awful thing to say. Why? Because underlying it is the assumption that only men can do computer science. Why on earth would you think that?

I first heard these words as an undergraduate, from someone I thought was a close friend. I felt sick to my stomach. I never felt imposter syndrome before that point. I loved technology, I was good at understanding how it worked, and how to make it do the things I wanted it to do. Up until that point, I assumed my strong technical abilities and grades was why I had been admitted into the program. Surely not my gender!

After I felt sick, I felt mad. Really mad! Who was this joker to tell me I didn't belong here? I'll show him.

Now, I'm fortunate, because I face adversity with stubbornness. It's just my nature. But most people are not like this. They get beaten down with a stick enough times, and they head for the hills. I can completely understand that, I've had my moments.

Here's the thing. Every time you say or even think these eight words, you're beating someone with a stick. You might think it's an innocuous statement, but really what you're saying is, "Go home dumb little girl."

Don't be a boorish bear.

In some ways, this type of article is good for young women in the field, because they figure if superstars like her can feel it, they can feel it too. i.e., "It's normal to feel this way."

Except, it's not normal to feel this way.

The reason we feel like we don't belong / aren't good enough, is because we've been encultured to believe this since Day 1. The message from the media is passive pink, and rarely are young women cast in roles of lead scientist in film and television. The whiz computer genius in a show usually looks like this:

"That doesn't look like me. Also, he seems really unhappy. I don't belong in computer science."

Readers protest, "But it's just TV! It doesn't matter!"

But it does. This is how kids choose careers. As much as we'd like to think that our annual science outreach visit to our children's classrooms hugely influences students' future career learnings, we're talking marbles vs. Large Hadron Collider. Hollywood is it.

So for the lucky few who manage to beat the cultural odds and enter our field anyway, they have one more major hurdle.

It's not the intellectual requirements of the job.

It's not work-life balance.

And it's certainly not babies!

Nope. It is eight little words that skewer you with a knife. Eight little words that knock you down in one fell swoop.

Eight little words that men never hear.

"You only got here because you're a woman".

Have you ever said this to someone? Have you ever thought this and not said it?

This is an awful, awful thing to say. Why? Because underlying it is the assumption that only men can do computer science. Why on earth would you think that?

I first heard these words as an undergraduate, from someone I thought was a close friend. I felt sick to my stomach. I never felt imposter syndrome before that point. I loved technology, I was good at understanding how it worked, and how to make it do the things I wanted it to do. Up until that point, I assumed my strong technical abilities and grades was why I had been admitted into the program. Surely not my gender!

After I felt sick, I felt mad. Really mad! Who was this joker to tell me I didn't belong here? I'll show him.

Now, I'm fortunate, because I face adversity with stubbornness. It's just my nature. But most people are not like this. They get beaten down with a stick enough times, and they head for the hills. I can completely understand that, I've had my moments.

Here's the thing. Every time you say or even think these eight words, you're beating someone with a stick. You might think it's an innocuous statement, but really what you're saying is, "Go home dumb little girl."

Don't be a boorish bear.

Sunday, February 9, 2014

profTime();

When I lecture, I usually begin by saying something about time. This is lecture x, we're n weeks into the course, we'll cover q next week, etc. At some point, x and n start to get large, and I have this meta moment of surprise that n weeks has gone by, and I start thinking about time.

If you ever go to an academic career mentorship thingy, you will inevitably see a picture of a three-legged stool, and the legs will be labeled with: Research, Teaching, and Service. Then there is this whole conversation about balance, and how when you go up for tenure/promotion, the Service leg should be, say, 2 inches long, and the others vary depending on where you are, but likely both will be very long. (The stool analogy, of course, breaks here. Floating? Frictionless pullies? Eh.).

Rarely do these career talks discuss the day-to-day aspects of professorial life. Some people, maybe Boice or Gilbreth, actually use(d) stopwatches to track every moment of their time. While I don't have any colleagues quite like this, I certainly detect a degree of time optimization awareness that is directly proportional to seniority. (Up until the Emerati, in which case the trend reverses).

What I find a bit troubling is that in the middle of that line are faculty at the associate level -- where they have all the same challenges as before, but now they also have a doubled service load. So they pretty much never have time for a shoot-the-hay chat. Which, frankly, is just about the most fun aspect of our job -- chatting with smart people who share your nerdy interests*.

I suppose I never envisioned a life of the mind, but certainly did imagine less busybusybusyAlwaysbusy culture. I think this is endemic to academia; I don't believe one style of institution or discipline plays a big role.

The good news, for any readers who are faculty-n00bs, is that there is a lot of "on-the-job training" as it were. After you've taught a class a few times, your preparation time dwindles down to nothing. After you've read 50 grant proposals / journal papers / grad applications / etc, you become crazy efficient at skimming and separating the cream from the cruft. And, of course, talks and posters and all that becomes a cinch.

Some things always take a lot of time no matter how you dice it. Writing strong grant proposals, handling personnel issues, and, for me, writing bios***. Though usually you reach a point where most things are good enough. You trust your students and collaborators a bit more than you started, and no longer need to read every word.

-----

(*) That's not to say I don't enjoy chatting with students. But, sometimes you want to talk about nerdy stuff with people from your nerd-era. e.g., the oldest grad students in my department don't get my lame jokes like, "Wow, that seminar felt like handshaking over a 1200 baud modem", or "Wow, that faculty meeting felt like compiling COBOL code on a PDP-11**."

(**) I'm not that old, I'm just making stuff up here. Though just last week, I overheard an undergrad saying something like, "OMG, it took 30 SECONDS to compile my program! SO LONG." And I'm just laughing.

(***) It's my BANE. And not the Christian kind, sadly. Oh, wait, that's Bale. Well, anyway, he probably has his own biographer, the lucky duck.

If you ever go to an academic career mentorship thingy, you will inevitably see a picture of a three-legged stool, and the legs will be labeled with: Research, Teaching, and Service. Then there is this whole conversation about balance, and how when you go up for tenure/promotion, the Service leg should be, say, 2 inches long, and the others vary depending on where you are, but likely both will be very long. (The stool analogy, of course, breaks here. Floating? Frictionless pullies? Eh.).

Rarely do these career talks discuss the day-to-day aspects of professorial life. Some people, maybe Boice or Gilbreth, actually use(d) stopwatches to track every moment of their time. While I don't have any colleagues quite like this, I certainly detect a degree of time optimization awareness that is directly proportional to seniority. (Up until the Emerati, in which case the trend reverses).

What I find a bit troubling is that in the middle of that line are faculty at the associate level -- where they have all the same challenges as before, but now they also have a doubled service load. So they pretty much never have time for a shoot-the-hay chat. Which, frankly, is just about the most fun aspect of our job -- chatting with smart people who share your nerdy interests*.

I suppose I never envisioned a life of the mind, but certainly did imagine less busybusybusyAlwaysbusy culture. I think this is endemic to academia; I don't believe one style of institution or discipline plays a big role.

The good news, for any readers who are faculty-n00bs, is that there is a lot of "on-the-job training" as it were. After you've taught a class a few times, your preparation time dwindles down to nothing. After you've read 50 grant proposals / journal papers / grad applications / etc, you become crazy efficient at skimming and separating the cream from the cruft. And, of course, talks and posters and all that becomes a cinch.

Some things always take a lot of time no matter how you dice it. Writing strong grant proposals, handling personnel issues, and, for me, writing bios***. Though usually you reach a point where most things are good enough. You trust your students and collaborators a bit more than you started, and no longer need to read every word.

-----

(*) That's not to say I don't enjoy chatting with students. But, sometimes you want to talk about nerdy stuff with people from your nerd-era. e.g., the oldest grad students in my department don't get my lame jokes like, "Wow, that seminar felt like handshaking over a 1200 baud modem", or "Wow, that faculty meeting felt like compiling COBOL code on a PDP-11**."

(**) I'm not that old, I'm just making stuff up here. Though just last week, I overheard an undergrad saying something like, "OMG, it took 30 SECONDS to compile my program! SO LONG." And I'm just laughing.

(***) It's my BANE. And not the Christian kind, sadly. Oh, wait, that's Bale. Well, anyway, he probably has his own biographer, the lucky duck.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)